By Linda Wing, PhD

Dr. Wing spent more than 45 years working to transform public schools in order to enable students in the nation’s cities to learn and achieve at high levels. She is an OLLI @Berkeley member and volunteer.

Grammie was a storyteller. Born in Mississippi, she found herself parentless at the age of 14. She worked as a nanny in New Orleans before being drawn to Chicago as part of the Great Migration, a mass movement of blacks from the south to the north that began in 1915. 20-year-old Grammie was among those who doubled the city’s Black population to 110,000 in only two years. She loved regaling her granddaughter Claire Hartfield about her life in Bronzeville, a seven-by-thirty block area on the South Side of Chicago that had emerged as the cultural and commercial hub of the rapidly growing Black community. King Oliver and his jazz band, the Olivet Baptist Church, the Wabash YMCA, the Binga Bank, The Chicago Defender— and Grammie — all flourished in Bronzeville during the 1920s. Claire was imprinted by Grammie’s vivid and joyful stories of her young adulthood. At the time, she was on the cusp of coming of age in Chicago as well, albeit two generations later.

Throughout time and across the world, Grammie and other elders have recounted stories to younger generations, stories that enable them to reflect on, mourn, and celebrate essential moments in their lives, stories that often become family memories that nurture, connect, strengthen, and encourage their descendants going forward. Recent research illuminates how this intergenerational transfer may occur. Functional MRIs indicate that the brain activity of the story-listener synchronizes with that of a skillful storyteller, not just in the language processing areas of the brain, but also in the neural networks that process emotion, complex information, and even motor activity. Neurologist Uri Hasson states that, in the joint act of storytelling and story-listening, the two brains “click” and become similar “in the ways that capture the meaning, the situation, the schema – the context of the world.” Mutual understanding is engendered, and what is understood tends to be retained in memory and used as knowledge in the future. Storytelling is powerful; it is rooted in the past and also affects what has yet to happen.

In the case of Claire and Grammie, the ”click” seems to have had extraordinary effects. Not only did Claire come to enjoy relating stories to her daughters when they were young, but she also began recounting stories to youngsters everywhere.

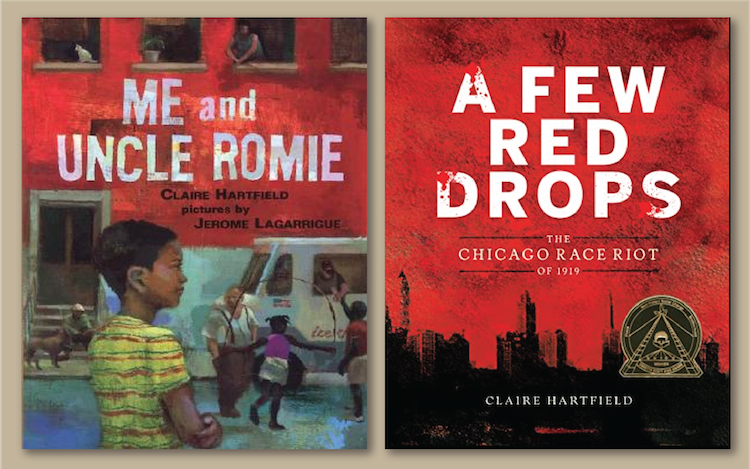

Published in 2002 and illustrated by Jerome Lagarrigue, Me and Uncle Romie is Claire’s book for five-to-ten-year-olds. She was inspired by the renowned artist Romare Bearden. Claire recognized Bearden’s work as a form of storytelling. Rather than words, Bearden used collage. In Me and Uncle Romie, Claire introduces readers to a young protagonist named James:

James travels alone to New York City to spend the summer with Uncle Romie. Both the city and his uncle are strangers to him. How will the summer unfold? On his return trip home to North Carolina, James opens a gift from his uncle. It’s a collage of their summer adventures together. James makes a collage too. It’s a gift for Uncle Romie depicting James’s favorite memories of him.

Me and Uncle Romie is inventively comprised of intergenerational stories told without words. The stories are doubly intergenerational; they travel from the older generation to the younger and back. Storytelling is powerful; it is generative of more storytelling in different media.

Claire followed Me and Uncle Romie with yet another book, A Few Red Drops: The Chicago Race Riot of 1919, written for young adults. Published in 2018, A Few Red Drops is the direct descendant of a story of chaos and courage told by Grammie to Claire:

Aboard a cable car going home from work, Grammie sees angry people flooding the streets. The cable car gripman drives posthaste through the crowd, ignoring all the stops, until the trolley reaches the end of the line. Now miles away from the mob, the gripman and his cable car are unscathed and safe. But Grammie is forced to walk miles back to her home through the night. It is the first day of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. The unrest does not end until three o’clock in the morning. The quiet is only momentary.

Grammie’s fraught eyewitness account of the beginning of the weeklong 1919 riot flashed through Claire’s mind many decades after the tale was recounted, nearly a century after the horrendous event occurred. What was the spark? It was 2014: Claire was watching CNN. For days – indeed, a week – she saw rioters protest the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

To understand Ferguson, Claire looked first to learn from Chicago. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “A riot is the language of the unheard.” Whose voices had gone unheard in Chicago? Were there untold stories of ancestors like Grammie that if brought forward to the present might collapse the distance of time and “click” with story-listeners today?

On the opening page of A Few Red Drops, the author introduces readers to John Turner Harris. 14-years-old, John lives in Bronzeville. It’s July 27, 1919, and the temperature is 96 degrees. John and his friends Charles, Lawrence, Paul, and Eugene head towards Lake Michigan to cool off. Their destination is the beach at Twenty-Sixth Street. The beaches along the lake are not officially segregated, but it’s widely known that the Twenty-Sixth Street beach is for Blacks. The next beach at Twenty-Ninth Street is for whites.

Rock throwing ensues between Black and white beachgoers disputing the invisible line between the two stretches of sand. One of the rocks strikes Eugene in the head. One moment, he’s swimming, the next moment, he is lost underwater. Desperate to save their friend, John and the other boys swim back to the beach and alert the lifeguard, who launches a search boat. The boys seek help from a Black police officer who is passing by, drawing him to the Twenty-Ninth Street beach where John had seen the white rock thrower headed. The white police officer working at the white beach overhears the boys. John spots the rock thrower and points him out. The white officer makes no arrest. He also prevents the Black officer from taking action.

Meanwhile 17-year-old Eugene’s lifeless body is found. He is brought to shore. A riot ensues.

“The Color Line Has Reached the North,” Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1919

A week later, 23 Black and 15 white people are dead; 342 Black and 195 white people are injured; hundreds, possibly 1,000 or more, are homeless – their houses have been looted and damaged, many by arson. The violence is far from unprecedented. Between January and May alone, three Black men were senselessly killed, likely by white gang members; Blacks were pelted with rocks when they visited city parks; and unknown perpetrators bombed ten homes and real estate offices to thwart Blacks from moving out of overcrowded Bronzeville.

The Illinois governor establishes a 12-member commission of Black and white civic leaders to investigate root causes and make recommendations. At the same time, indictments are brought against 128 people for riot-related crimes. One-third of the indicted are white; two-thirds of the riot victims are Black. The grand jury finds this ratio unbelievable, observing that Black people “couldn’t have a created a riot by themselves.” Many if not most are afraid to bear witness. 14-year-old John Turner Harris, for one, does not tell his story until 50 years later, so dangerous and frightening is truth-telling in that moment.

John Turner Harris’s harrowing story comes to light in A Few Red Drops. It is one of many connected narratives of Chicagoans who figured in 1919 and in the earlier years of the city’s history back to its beginning. As well, the author points readers to “echoes” of 1919 that can be heard in the present. All in all, Hartfield gives texture and dimension to the story of Chicago writ large – how it was developed and shaped by Blacks migrating from the south, Irish immigrants, meat packing magnates, union organizers, gang members, newspaper editors, church leaders, settlement house volunteers, civil rights activists, domestic workers, and political bosses. Sixty-five photos, editorial cartoons, and documents curated by the author enable readers to literally see the stories unfold.

The story of Ida Wells-Barnett is the book’s throughline. Born into slavery in Mississippi, Wells-Barnett became an investigative journalist who exposed lynching, the public extrajudicial acts of whites to murder, terrorize and control blacks in the 19th and early 20th centuries. She moved from the south to Chicago in 1893, where she became a vital and enduring force for community development in all its forms, including women’s suffrage, kindergarten for young children, employment and social services for newly arrived migrants, and collective action on behalf of freedom and equality. During the 1919 riot, Wells-Barnett witnessed police indifference to attacks on Blacks, called them to account in her reportage, and served as a trusted conduit for the testimonies of Black community members too fearful to speak publicly to the riot commission.

Grammie inspired her granddaughter Claire Hartfield to follow her example of storytelling across generations. Hartfield gives readers Ida Wells-Barnett, arguably the ancestor of all those who tell stories that turn “the light of truth” on wrongs and injustices. The essence of Wells-Barnett’s life story and the words she herself wrote resound with power across the generations:

“Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.”

Storytelling is powerful, infinitely.