Thomas Gold is professor emeritus of sociology at UC Berkeley, where he also served as Associate Dean of International and Area Studies, Founding Director of the Berkeley China Initiative, and Chair of the Center for Chinese Studies. From 2000-2016, he was Executive Director of the Inter-University Program for Chinese Language Studies, a consortium of 14 American universities which administers an advanced Chinese language program at Tsinghua University in Beijing. He is teaching “Chinese Cinema: Reform-Era Revolutionaries” with us this spring.

Were you in China when these reform-era films emerged?

I was living in China in 1979, when they began to show films from the 40s, 50s and 60s, many of which had been criticized for political incorrectness one way or another. There were some new films being made at the time, but they were still stuck in the same ideological trap. In the summer of 84, I was in Hong Kong when Yellow Earth by Chen Kaige came out. Friends had told me that there was this revolutionary film I had to see. When I did, it just blew me away. It was one of these daring explorations of different aspects of Chinese history, and a rewrite of the key elements in the Communist Party's history. Yellow Earth opened the door to a flood of films of that nature, which interrogated China’s official line.

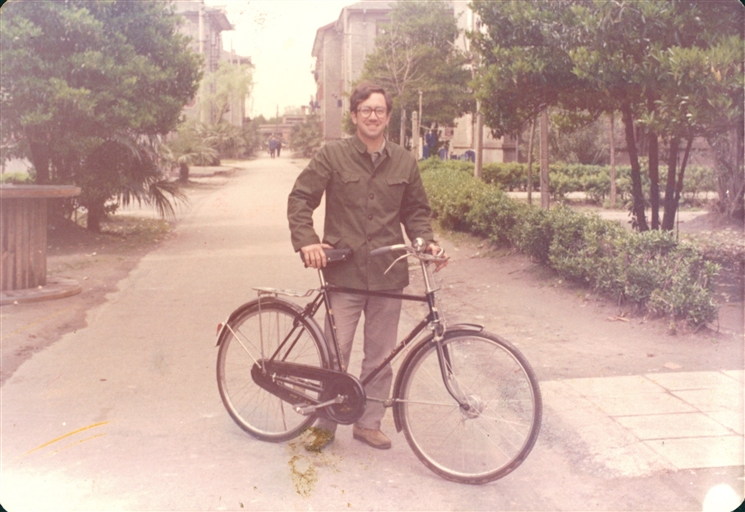

Tom Gold in 1979 at Fudan University in Shanghai

You recommend that members read Mao Zedong's speech "Talks at the Yan'an Forum on Literature and Art.” Why’s that?

It provides context for what filmmaking was like before the reform era. Mao gave the speech in 1942 when the Communists were holed up in Northwest China in a very poor, backward area. He was worried that too many intellectuals were going there because they thought it was cool to participate in the revolution and that they could have free reign intellectually and creatively. Mao was basically calling them out, saying, “well, here are some issues that I want you to discuss. Who are films for? Who is art for? You, intellectuals, you don't really understand the common people. You have to integrate yourself with the workers, the peasants, the soldiers, and then you'll produce art that serves the party.” That directive created a cage that lasted until the mid-1980s and is now reasserting itself. Certainly over the last decade.

What are some of the films you’re going to discuss?

Red Sorghum by Zhang Yimou is one. It’s an award-winning, unbelievably powerful film. Still Life by Jia Zhangke is another. He did a number of films that dealt with unexpected aspects of life in China in a very confrontational way. He still makes films, but they aren't allowed to be shown in China. I had trouble narrowing the list because there are so many good films of the era. I ended up choosing ones that, together, give breadth to different aspects of Chinese society.

You’re not showing the films in the class, correct?

Right. Members will stream the films on their own with a letter from me about what to look for as they watch. Then in class I’ll provide political, cultural and historical background about what was happening in the country at the time, and we’ll discuss the films specifically.

What do you hope members take away from the course?

That China is not a monolith. That there is tremendous diversity — rural and urban differences, income diversity, gender diversity, wealth, status, internal migration, consumerism. It’s all there, captured in these films. I hope people walk away with a much more complex understanding of what’s going on in China, and how hard it is to manage. China operates on so many different levels with so many issues and challenges. It’s much more complicated and nuanced than I think many people realize.

Going back to the beginning ... what sparked your interest in China?

I’m from Cincinnati, Ohio. As a kid, I’d never been out of the country or even on an airplane. When I was a freshman at Oberlin, I took a course on Asian history, which I really enjoyed. After that, kind of on a dare, I took a Chinese language course. From Day One, I was hooked and took everything I could related to China. In the summer of 1969 after my junior year, I did an Oberlin summer program in Taiwan to work on language. In those days, you couldn’t go to mainland China. I loved being in Taiwan, and loved being in Asia. After I graduated, I got a fellowship to return to Taiwan to teach English for two years. That’s when I realized that I really wanted to go into an academic career, and I wanted it to have something to do with China writ large.

Sounds like that Chinese history class freshman year really set you on your path.

Absolutely. It changed the whole trajectory of my life. One reason I enjoyed teaching freshman introductory sociology at Cal was telling all these impressionable young people to get out of their comfort zones, to explore, to talk to professors, to do things that feel different and strange. Who knows where it’ll lead. Leaving my comfort zone and taking that course certainly led me on a path I couldn’t have imagined as a kid.