91-year-old Lillie Braudy has been an orphan (at 15), a realtor, dress designer, corporate employee, deli owner, agent for artists, and much more. And now she’s a writer. She developed this reflection in an OLLI course, “Writing in Place,” taught by Cecilia O’Leary and Tony Platt in the winter of 2021.

Lillie Braudy, age 10, New Bedford, MA

Ten years old, I could barely keep myself from shaking with fear and excitement. I did everything my mother Annie told me to do after Dad had finished his dinner – a shot of Four Roses, meat, potatoes, and stewed fruit laced with brandy. He lay on the couch and I massaged his tired, sore, swollen feet encased in stinky wool socks. This nightly routine was the only time we ever touched each other. Usually I rushed the job, but this night in July 1940 I was slow and careful so that he would fall asleep and not discover our absence until the boat sailed.

My father Morris emigrated from Russia in 1915 and married a rich man’s daughter — Annie Teresa Goldstein, my spoiled mother. He opened Braudy’s department store in New Bedford, selling everything from corsets to my outfits. He did all the buying from drummers and jobbers, while my mom ran our home and helped him run the store. I worked there part-time too, learning to wait on customers and straighten up everything. The business did well enough that Dad could afford to bring five brothers and five sisters from Bialystok to the United States.

That night in 1940, Mom who never took me anywhere from our home on Pleasant Street – not even to the Wednesday matinee in Boston that she went to alone – was taking me to New York City on the Colonial Line. Such an extravagant way to travel! The Big City was glamorous compared to our house where we washed clothes in the cellar and hung them out to dry next to the coal bin or outside if the weather was good. It was hot in the summer. In the winter, we had a furnace our upstairs neighbor stoked for us. My nose was always filled with soot. My mother’s helper Stephanie lived in the upstairs cupola where she had no running water or toilet. When World War II started, she left us for work at one of the mills making clothes for the military.

Braudy family sans one brother

I wish that I could have left too. I was hated by the nuns who begrudgingly taught me piano and by classmates who pulled at my clothes and called me a Jesus-killer. My mother frightened me most of the time. My father sent his three sons to Colby College in Waterville, Maine, making them hitch-hike to school winter and summer. He didn’t believe in giving them money unless they earned it. I knew my life was going to be stuck with my parents never allowing me to leave them unless Prince Valiant showed up.

Mom waited outside the house until Dad was asleep, then waved me out to join her when the taxi arrived a block away. “We’re going to have a wonderful adventure,” she said. But before our getaway, Dad woke up, read my mother’s note, and rushed to the boat to take us off before it sailed. He was a stern man who wanted everything done his way. Obediently. “Go and hide, your father is here,” yelled my mother. “Run to the ladies’ room so he can’t find you.” I ran. I was petrified that I would get strapped for disobedience like my three brothers, especially Ralph for hanging out with his non-Jewish friends.

My father boarded the ship intending to bring us home. My mother somehow changed his mind, explaining that we’d be back by Saturday for the big business day. When I sensed that he was placated, I left my hiding place. “Please, daddy,” I pleaded, “please save me my Prince Valiant comics from the New Bedford Standard Times.” This prince was going to rescue me from the horrors of living with my hateful mother, who beat me, boxed my ears, and locked me in a small, dark blanket closet if I did anything to annoy her. I spent many hours daydreaming of being spirited away from Pleasant Street and my mother by Prince Valiant. Even at aged ten I sensed I had to make it on my own to be rid of them both.

Dad left the ship.

My mother took center stage in full swing in the large common room filled with passengers. She played the piano and ordered me to tap dance and sing. Annie was always making me perform in front of strangers and I hated her for it.

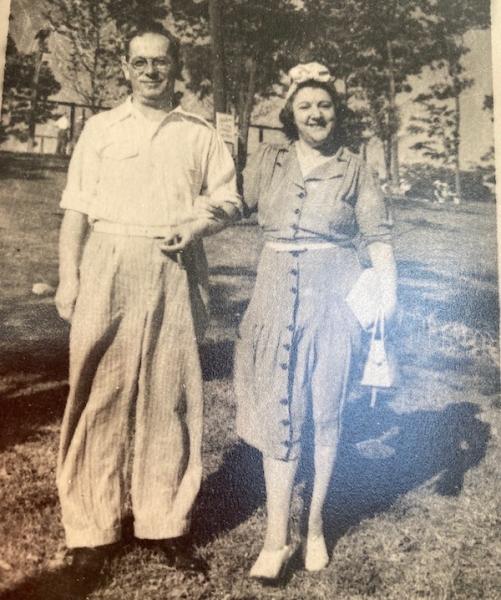

Dad (Morris) and Mom (Annie)

I don’t know how my mother did it. I always had to dress in outfits from Braudy’s – horrible colors of brown and tan, terrible styles. For this trip, she bought me the most beautiful shorts with a matching short jacket with a hood from the local upscale Star Store. If he had known, my father would have been wild with anger that Annie spent his money at another establishment. She hid the package until we reached New York.

I don’t remember if cousin Bertha met us at the ship in New York the following day or if we took a taxi to Adele and Bertha’s apartment in the Village. But I do remember that my father would never permit Bertha to visit with Adele in New Bedford because he said Adele was no good. She was very dark skinned and very tall. Today, I think he knew they were lovers and would not permit this non-Kosher arrangement to become a part of our home in New Bedford.

In New York, my mother was ecstatic, never on my case. We visited the World’s Fair where I remember very little except one building called the “House of Tomorrow.” Everything was electric. When the lights were turned off in the auditorium, my white outfit glowed. I thought it was the most beautiful house I had ever seen. I was looking at heaven.

The next day, Annie announced that we were going to the theatre. I assumed she meant the movies. She took me for lunch to Horn and Hardart’s Automat in Times Square which advertised “Less Work for Mother.” I was amazed that you could see what you were going to eat and pay with coins.

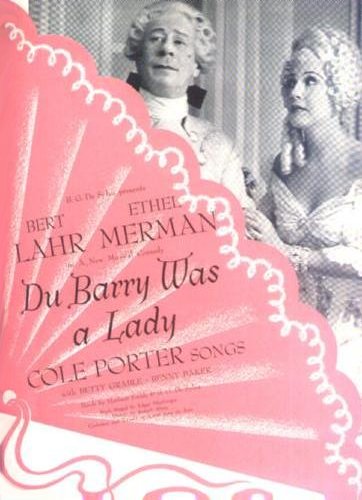

Then the “piece de resistance” of my life: A live Broadway show called “Du Barry Was a Lady” with Bert Lahr, Ethel Merman, and Betty Grable, music and lyrics by Cole Porter. Everything I saw and heard was a miracle. The overture and music were unbelievably beautiful. I had never heard such sound, never been transported to such complete happiness. I never imagined that such pleasure was unfolding in theatres all over New York. The song “Friendship” made me happy and sad all together. “If you’re ever in a jam, here I am.” I wept and wished that I had a friendship with my mother.

Back home in New Bedford, I wished my parents dead and they obliged.

Dad had always been a sick man. He had his first heart attack the year after I was born. Three years after the miracle in New York, he died. Two years after his death, on a sunny summer morning, I found my mother on the floor in the bathroom, half paralyzed and half regular. She’d had a stroke. Mom had huge brown eyes. I was terrified looking at her non-paralyzed part, seeing the enormous eye looking at me. She and I were alone in the house. I was fifteen years old. She died two weeks later.

Lil with long legs

Whatever my mother did to me after we returned to New Bedford in 1940 – hitting me, locking me up in the closet, showing me buildings that she said were reform schools – I was determined to be my own person and never forget that night in New York when I left the theatre tap dancing, swinging my arms, doing ballet poses, laughing and singing and dancing into the street. In my head I could still hear the orchestra playing.

In spite of all the horrors, my mom brought me to the best thing ever in my life – Live Theatre!

And for that I forgive her.

The OLLI @Berkeley Blog showcases the voices and perspectives of our community (members, faculty and staff) as well as news from and about OLLI. Personal observations of life in this moment, of growing older, of self-discoveries large and small are just a handful of possible areas to explore. Read more.