February 2023

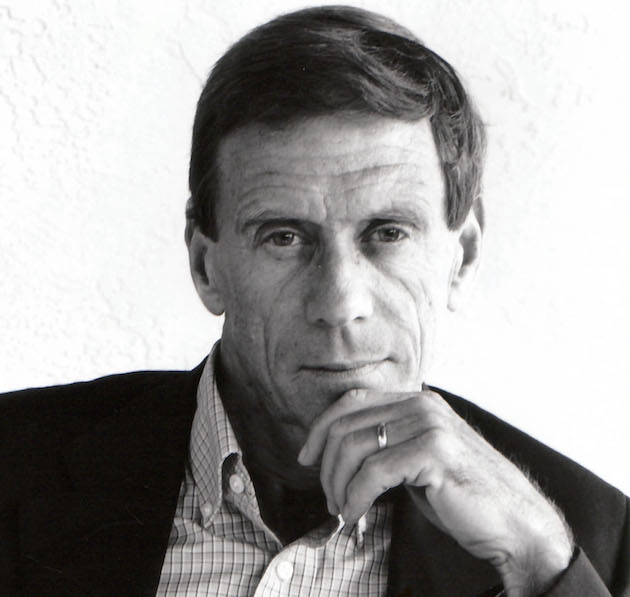

Bill Smoot received his PhD in philosophy from Northwestern University, specializing in existentialism and ethics. A lifelong teacher, for the past decade he has taught at Mount Tamalpais College (formerly Prison University Project), the college program at San Quentin State Prison in California.

You recently wrote a book, Conversations with Great Teachers. What inspired the idea?

I’ve always been a fan of Q&A interviews, and in particular I loved the works of Studs Terkel, especially Working. I remember hoping he would do a book on teachers, but after he stopped writing I got the audacious idea of doing such a book myself.

Early in the process, I realized that nearly everything we do—from tying our shoes to baking a cake to arguing a case in court—results from having been taught to do it. So I branched out beyond school and college classrooms to other venues. As a result, the book contains interviews with people who teach making horseshoes, wrestling alligators, playing the infield in the major leagues, exotic dancing, brain surgery, firefighting, and film acting. It was exciting for me to interview such an amazing array of teachers. I felt a swelling of pride in the great teaching that happens daily throughout our society.

What’s the magic that makes a teacher great?

Though the ingredients are many, passion is key—passion for one’s students, passion for the activity of teaching, and passion for the subject matter.

One epiphany I had is that teaching is not a separate skill but an aspect of expertise in a subject. The ed-school model implies the latter—you go to the biology department to learn biology and then to the education department to learn how to teach it. But suppose it’s more like this: The highest level of wisdom one can achieve in biology (or anything else) is to know how to teach it to others. Teaching emanates from expertise rather than being ancillary to it. In many of the teachers I interviewed, I found that their expertise in their subject area was the foundation of their teaching.

Whether it’s horseshoeing, dancing the role of the Swan Queen, winning an Oscar as an actor, making pastries, or believing math is beautiful, these experts loved their subject so much that they just had to teach it.

You’ve taught at the Mt. Tamalpais College program at San Quentin State Prison for a decade. What drew you there, and what have you learned from the experience?

Actually, doing my book on teaching drew me there. I interviewed Rhodessa Jones, a Bay Area performance artist teaching incarcerated women. I found her so inspiring that I looked for a place where I might teach incarcerated people, and I found the program at San Quentin.

What’s surprised you most about teaching in prison?

The big surprise was the lack of surprise. The men I teach are regular guys, albeit regular guys who have done some very irregular things. The ones who find their way into the San Quentin college program are very serious about learning and improving themselves, and I respect and admire them for that. To me, they are not criminals but human beings who have committed crimes.

Since I teach discussion-oriented humanities classes, many men are forthcoming about their life stories and their crimes. In many cases, it’s easy to see how they committed the crimes they did. I grew up in a small town in the fifties, and the gateways to prison were not so ubiquitous then as they are now.

Though I have considered myself a leftist since I came of age politically in the sixties, I feel very frustrated with the current obsession of some leftists with the intellectual minutiae of the culture wars. I wish we all could focus on what I call the Big Six needs to combat inequality: good jobs, decent housing, good schools, good health care (including for psychological and substance abuse issues), a good living environment (parks, convenient stores), and law enforcement that serves and protects. I wish the energy directed toward becoming more woke than thou could be redirected into those Big Six. I sometimes worry that DEI programs, however well-intended, function to divert attention away from real, material inequality.

Has your work at San Quentin changed or clarified your view of imprisonment?

One of our great problems as a country—and this includes ordinary people as well as those in power—is that we don’t really know each other well enough. Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, speaks of the power of proximity, getting close to people. Reading about the marginalized has value, but it must be accompanied by getting proximate. We need to talk, to walk each other’s neighborhoods, to work shoulder to shoulder on common projects. If you’re a liberal, invite a MAGA person to have a beer. We cannot understand those unlike ourselves unless we get close to them. Teaching at San Quentin has allowed me to get more proximate to incarcerated Americans, whose reality is not truthfully depicted in movies and on TV.

Sometimes people tell me I’m doing a good thing in teaching pro bono at San Quentin. I appreciate their good wishes, but the fact is—and I really believe this—that in my work there I receive much more than I give. I receive the gift of being able to help. I receive the pleasure of teaching. I receive the fellowship that is a part of a good classroom. And I receive the opportunity to understand by being proximate.

What do you hope OLLI members take away from your course on the morality of prison?

The issues involving crime and punishment are difficult and complex, requiring good thinking from the disciplines of criminology, psychology, political science, law, economics, and even neuroscience. It is sometimes said that philosophy is the mother discipline, a foundation from which all the others are born. This course will employ moral philosophy to help us ask what we ought to do about the wrong-doing of crime and whether prison is a moral response to that wrong-doing. While the course may not provide answers, it is my hope that it will help us clarify our thinking and focus our eyes on the prize—which is justice.