Susan Alunan, Ph.D. teaches political theory, urban politics, and activism. Previously, she staffed, then led the SF Urban Institute, developing creative approaches to critical issues such as housing, community development, and educational equity. She is teaching, “SOMA’s Other Story: History, Culture & New Arts” with us this summer.

There are a lot of neighborhoods in San Francisco. What made you want to focus on South of Market (SOMA)?

At the SF Urban Institute at San Francisco State University, I liasioned with communities, nurtured multisectoral partnerships and created programs. Starting in the Mission, Visitacion Valley and the Bayview, I became embedded in communities throughout San Francisco, including the South of Market.

I’m Filipino American, born and raised in Bernal Heights. But I learned a lot about being Filipino American through the immigrant experiences of those living in SOMA.

I’m Filipino American, born and raised in Bernal Heights. But I learned a lot about being Filipino American through the immigrant experiences of those living in SOMA.

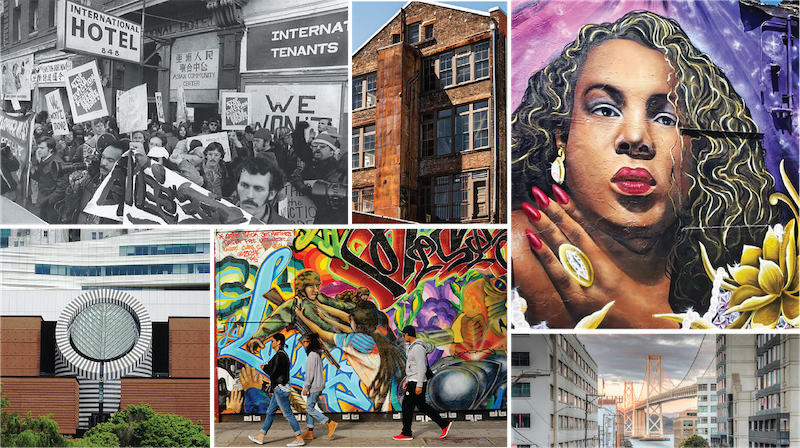

South of Market has welcomed waves of immigrants going back to the 19th century. Changing global politics, war, and immigration quotas made SOMA a first US entry point for some and a final destination for many: Irish, Italian, Chinese, German, Eastern European, Latin-X, Lebanese, Filipino, and Southeast Asian immigrants and refugees began their lives as Americans there.

Until the passage of the Housing Rights Act, “whites-only” housing codes in certain neighborhoods relegated immigrants and people of color to central and southeast neighborhoods such as SOMA.

I’m attracted to SOMA’s stories, and the neighborhood’s successful fight to preserve a sense of community – for the people who remain amidst urban renewal and massive new development, as well as for the people forced to move away who return for celebrations, a sense of community and belonging.

How has the community evolved over time?

The story of SOMA is the immigrant and working class story of San Francisco. Unless you were Native Ohlone or Miwok, you were a newcomer. So, SOMA represents a beautiful microcosm of the San Francisco that was, and the city we hope it can be again. Before mid-century redevelopment, it was a place where generations of people could find work, raise families and build their American dream, whatever their origin. SOMA is about interwoven narratives of memory and loss, history, hope, a new home. Her story lives in the mix of cultures and strong communities, of urban renewal, pressure, resistance, displacement, erasure, and finally, rebirth.

SOMA was a place for the working class and the newly arrived. Before the economy shifted from light industry to finance, big tourism and tech, SOMA housed thriving families and workers in a strong labor town. It also attracted merchant marines, longshoremen, and elderly agricultural workers in residence hotels such as the Delta and the International Hotel in adjacent Manilatown.

Many in the hotels were single men and the elderly. For them, SOMA was a place of solidarity and conversation, where you could eat, shop, get your hair cut and your clothes cleaned. They lived in a community where people knew you and could help. They were not isolated.

Can you talk a bit about the International Hotel in Manilatown?

I’m going to devote an entire class to the civil rights activism that began with the redevelopment efforts to raze the I-Hotel for a parking lot. The long eviction fight symbolized the immigrant struggle for identity, self-determination, and civil rights. It involved Filipino and Chinese residents and committed rights activists of all stripes: Asian Americans, African Americans, Latin-X Americans, the Jewish community and other religious groups, gays and lesbians, students, affordable housing and neighborhood activists fought together and the I-Hotel was successfully rebuilt decades later.

How do you experience the neighborhood today? What is the feeling of the place for you?

Sometimes I experience sadness because of the loss of community, the loss of affordable housing, drug encampments, of people struggling to exist. Poverty and despair are juxtaposed against vast wealth, lofts, and new tech kids with money who seem inured to the humanity and history there. Recent cultural hubs such as SFMOMA, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, the ballpark, new galleries, and Michelin-starred restaurants are wonderful if you can afford them, but they come at great cost.

I also see folks who’ve lived there and the agencies that serve them, more recently Chinese, Latin-X, Southeast Asian, and Filipino folks, but there are fewer. Rents are higher for fewer affordable units; the cost of living is prohibitive.

Ultimately, though, I see hope and new dynamism. A new generation is building community in new creative ways. New voices fight for affordable housing, justice, equity and the preservation of neighborhood culture while creating new art venues and working with existing support organizations. SOMA’s formal designation as a Cultural Heritage District is bringing fresh resources to do this work.

What would you like OLLI members to take away from your course?

I’d like OLLI members to experience SOMA through this “other story,” the interwoven narratives of the people who have lived, worked, fought, and called SOMA home.

The San Francisco I grew up in was a place where it was possible for us to live together, work together, get educated together. The city has changed so much since then because of changes to the economy, workforce, development policies and displacement. We’ve lost a lot of battles. But we are winning important ones, too.

I’ve worked with many young people in SOMA and other neighborhoods; they inspire me with their new vision, passion, creativity in a time of flux for the city. In the last session we will talk about the dynamic new arts scene in which a new generation continues the work of building community in exciting new ways. I think their story will inspire OLLI members to experience the South of Market and the city in new ways, too.