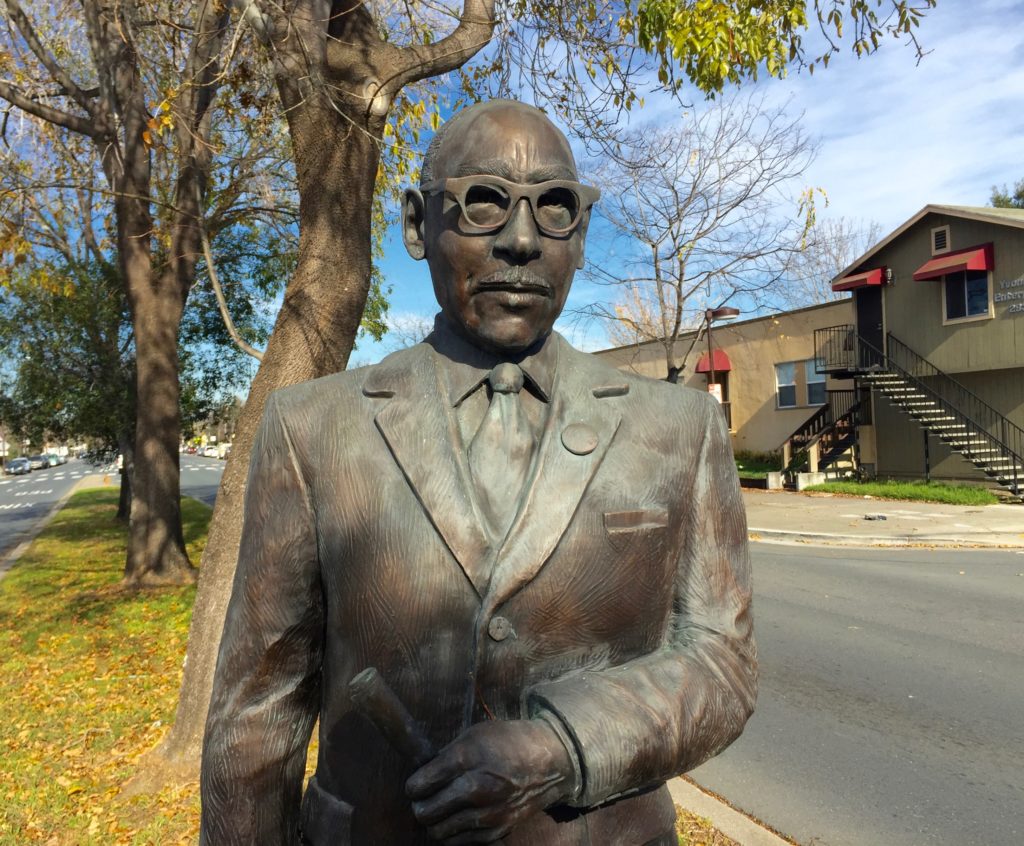

A statue of Byron Rumford was created by Dana King and erected across the street from the site of Rumford’s Pharmacy near Sacramento St. and Ashby St. in Berkeley.

Recently, I participated in UC Berkeley’s brand-new Black History Tour. OLLI friends joined me. Gia White, our guide and co-creator of the tour, provided insights into the experiences of students and faculty members dating back to 1881. It was then, 143 years ago, when the first Black student enrolled at Cal. We learned about remarkable individuals within the contexts of their times, whether the first decade of the Great Migration beginning in 1910 or the tumultuous year of 1968 when students demanded a Black Studies Program. The tour is part of the university’s effort to research, illuminate, and celebrate Black lives at Cal. Inspired to learn more, I began to explore Berkeley’s Black History website. When I landed on a webpage listing oral histories of Black alumni, I was excited to learn that Byron Rumford was a Cal graduate. When I was a junior in high school, Assemblyman Rumford was my hero. He was a key figure in my coming of age.

Who Was Byron Rumford?

Byron Rumford was the author of the 1963 California Fair Housing Act, also known as the Rumford Act. The law, as he originally envisioned it, was Assemblyman Rumford’s moonshot. He aimed to do no less than prohibit racial discrimination in the sale and rental of public and private housing throughout the state. When Mr. Rumford introduced a bill towards that end, it was met with fierce opposition. A battle ensued.

The resistance was led by state legislators who were allies of a 500-pound gorilla – the California Real Estate Association. They proposed more than 100 amendments. The bill survived the avalanche, but its scope was narrowed to focus on “homes only if they had publicly assisted financing” and privately financed housing “with not more than four units, one of which was occupied by the owner.”

After the modified bill passed and became law, resistance to fair housing continued. In 1964, a majority of California voters passed Proposition 14. The proposition voided the Rumford Act by creating a constitutional right for California property owners to refuse to sell, lease, or rent residential properties to anyone, for any reason. A vigorous court challenge led to the California Supreme Court’s 1966 decision to declare Proposition 14 unconstitutional because it violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. The decision was appealed, but the US Supreme Court upheld the state court’s ruling in 1967.

A mural on Sacramento St. in Berkeley honors William Rumford

Ultimately, Assemblyman Rumford prevailed not only in California but also the nation. The Rumford Act became the progenitor of the landmark Title VIII of the 1968 Civil Rights Act. Title VIII prohibits discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, color, religion, sex, disability, family status, and national origin. Byron Rumford’s moonshot had finally landed.

How Did the 16-Year-Old Who Was Me Come to Revere a Fair Housing Champion?

In 1954, my parents attempted to buy their first home in Sacramento, California. They made several offers, all of which were rejected on the basis of our family’s race. Upon overhearing Mom and Dad deciding to persevere in their search, my younger sister, five-years-old at the time, gave them this advice: “Next time, don’t tell them we’re Chinese.” My parents laughed, their tension relieved by this unexpected moment of tragicomedy. They gave my sister a hug of thanks for her love and loyalty.

Mom and Dad eventually succeeded in buying a house in a new development. After our family moved in, my parents received a petition signed by the residents on our block. The document indicated that life would be better for the children in our family and the children in their families if our family left the neighborhood. We were the first people of color to move into the development, and it was clear that we were not welcomed. It was under these circumstances that I began third grade at the neighborhood school three blocks away from home. I was the school’s first and only student of color. It’s a fact of American life: when housing is segregated, schools are segregated.

Years later, at age 16, I found solace when I went on a high school field trip to the state capitol. My teacher, Mr. Mahan, took our US Government class to a legislative hearing on a new bill, the fair housing bill. It was at the hearing that I learned about Assemblyman Rumford and his commitment to ensure that every family, including mine, would enjoy fair housing opportunities, not exclusion based on race. He understood that home is where the heart is; it is, at once, a basic human need and a symbol of the American Dream.

I learned firsthand about opposition to fair housing as well. The chair of the committee conducting the hearing ejected a priest and two nuns who stood in silent support of the bill to stop what he claimed was their disruption of the proceedings. Subsequently, the chair publicly announced that his committee would never approve a bill prohibiting discrimination in private residential housing.

Assemblyman Rumford was calm, deliberate, and tireless in sustaining his efforts to bring fair housing to California residents. In the face of a powerful real estate industry, he rallied the support of ordinary people.

That Assemblyman Rumford made the concept of fair housing important and meaningful to ordinary people was evident in the persons of the priest and nuns who had been ejected from the assembly hearing. They were not alone. One day, my teacher, Mr. Mahan, was absent from school. We students wondered why. When he returned to class, Mr. Mahan explained that he had been arrested for participating in a pro-fair-housing occupation of the capitol rotunda.

Concerned that the fair housing bill might be shelved at the end of the legislative calendar, Assembly Rumford mobilized key senators and assemblymen to make canny use of parliamentary procedures to advance the bill to roll call votes. On June 21, the legislature’s last day in session, the State Senate began a roll call vote at 11:00 pm. The fair housing bill was approved by a count of 26 to 16. The bill was then sent to the State Assembly where fair housing faced greater peril than in the senate. A roll call vote started at 11:38 pm. At 11:50 PM, the bill was passed – to a standing ovation, reportedly the first in the history of the assembly. The governor signed the Rumford Fair Housing Act into law on July 18, 1963. It became effective in September 1963.

And so it was that I came to heroize Byron Rumford. He was a key figure in my adolescent identity development. Because of Assemblyman Rumford, I discovered that my family was not alone in experiencing racial discrimination when trying to find a home. Equally important, I learned that families of color were not the problem. Racial inequalities were built into housing policies and markets across all localities. In Mr. Rumford’s example, I saw that the problem was not intractable. With measured leadership, he catalyzed collective action among ordinary people and elected officials to enact legislation to expand fair housing to all. Opposition was formidable, setbacks occurred, yet the assemblyman persisted. I am grateful that I was in the right place at the right time to learn these life lessons at age 16.

Afterword

Byron Rumford earned not one but three degrees from the University of California. He was awarded a Pharmacy G degree from the University of California San Francisco in 1931, a BA in political science from the University of California Berkeley in 1948, and an MA in public administration from Cal in 1959. Remarkably, Mr. Rumford was elected to his first term in the California State Assembly in that same year that he received his BA and won passage of the California Fair Employment Practices Act in the same year he earned his MA. The fair employment act was the first of two seminal civil rights laws that he spearheaded, the second was the fair housing act.

Clearly, Byron Rumford was determined to learn more in order to do more as a public servant. In the tradition of Black history at Cal, he placed extraordinary value on education as empowerment to advance equality, justice, and civil rights.

Linda Wing, Ph.D., is an OLLI @Berkeley member and volunteer who spent more than 45 years working to transform public schools in order to enable students in the nation’s cities to learn and achieve at high levels.

The OLLI Blog showcases the voices and perspectives of the OLLI community (members, faculty and staff) as well as news from and about OLLI. Please contact OLLI's Nancy Murr to learn more.